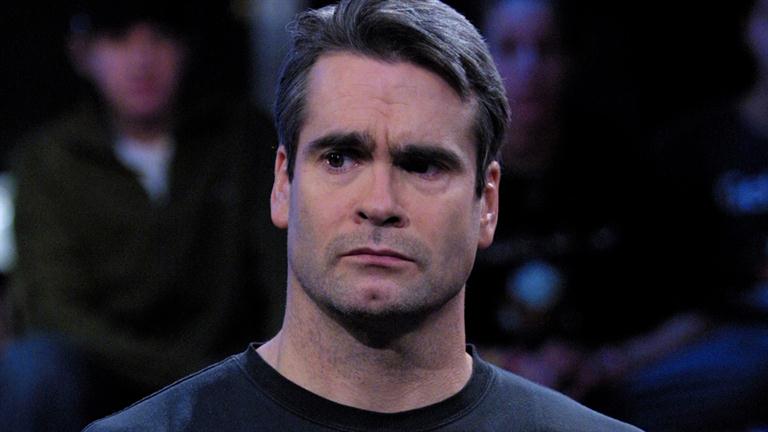

“I could grandstand and tell you I’m The Man, but I basically don’t have a life,” Henry Rollins tells me in a recent phone interview.

As usual, The Man is being too hard on himself. The rock legend, now in his early forties and still as tough as a fifty-cent steak, has it for sure going on. He recently completed an 88-show spoken word tour, two USO tours — one to Iraq and Kuwait, the other to Honduras — and flexed his considerable acting chops in a major motion picture. This is in addition to hosting a seriously-listened-to radio show that airs in Los Angeles, his intense schedule of record producing, the day-to-day running of his publishing company, and his Marine-like daily workout, which includes pushups using only his knuckles.

If I called him a Renaissance Man, would he kick my ass from here to Sunday? And would he have time to do it?

“I’ve been called a lot of things,” he admits, “as long as they don’t call me late for dinner.”

So what makes Henry run? Why – after a satisfying career as a music pioneer, actor, monologist, writer/publisher and business entrepreneur – would he not opt for a nice, cozy nap? Or at least a week on a chaise lounge at Sandals?

“I have a low threshold for boredom,” he says. “I’d rather do stuff than talk about doing stuff. The idea is to work vigorously. All my heroes work vigorously: Miles Davis, Duke Ellington. I’d rather do that than take three months off to find myself on some beach.”

Of course, there are things he won’t do. He recently turned down a six-figure offer from a Japanese liquor company — a la Bill Murray in Lost In Translation – to sit still for a whiskey advertisement (“I don’t hang out with alcohol,” he says). He also won’t do drugs or smoke cigarettes. That’s right. The front man for Black Flag, one of the most influential groups of the punk movement, is a teetotaler (I only hope he won’t kick my ass if I call him that.).

“I have never been tempted,” he says. “I have been drunk about three times. In ‘87 I tried marijuana for the one and only time. Tried LSD. Interesting. Can lose your mind. Something told me, ‘you’re not doing this anymore’ and I said, ‘right’ and I didn’t.”

He gets his high from working. He’s been doing it since he was ten, in the suburbs of DC. Dad was an academic (“he was tough as nails”), and his parents divorced when he was still in diapers. Henry came up rough and ready, the product of boys’ prep schools. Hard to believe now, but he originally looked like the “before” picture in the Charles Atlas ads. However, a history teacher (who was also a former Vietnam vet with six kills to his record) talked him into weightlifting, which he took to like a social outcast to a Black Flag concert. He bought his first workout equipment from Sears, which he could barely lift into his mom’s VW. Six weeks later, he could throw the equipment across the parking lot.

“Weightlifting was good for me in high school because I didn’t have to compete and you didn’t get laughed at,” he says. “I grew up skinny and raised on Ritalin. [The history teacher] was a male role model who was actually giving me a moment of his time. He wouldn’t allow me to look into the mirror [while I was training], and I didn’t. [Once I finally did,] it was a huge revelation that I made this [new body] happen. The confidence that came with that…all of the sudden you are being left alone at gym. I went to an all-boys pseudo-military school. I beat up and hospitalized a senior when I was in tenth grade, which is basically all the work you need to do for the rest of your life in high school. The seniors respected the fact that I righteously bloodied one of theirs. Your peer group is like, ‘yeah! One of our guys beat up an upper-classman.’ My last two and half years in high school were then pretty cool. It was like, leave the Ritalin boy alone.”

Rollins tried college for about a minute (“My fellow students were so boring,” he recalls. “It was really depressing. None of my classmates read. Everyone was concerned instead with beer and bongs. And I thought, fuck this, I’m not doing four years of this.”). Instead he experienced life on the minimum wage: “shoveling, parking, scooping, tearing, carrying.” He was even a taxi driver for liver samples for the National Institute of Health. All the while, he poured some sugar into the bank. He also met a savvy and trustworthy financial manager along the way, who helped him deal with the dollars, which eventually came in.

“I’ve been saving since I was ten,’ he says. “I don’t have extravagances.”

Of course, extravagances is a relative term. Rollins is not exactly Amish. This simple man does own three houses, but in all fairness, two of those houses are filled with his vast music collection. However, he didn’t earn his real estate by being a rebel without a clause. He’s a damn astute businessman. Of his place in the music biz, he says, “I [don’t want to sound like] the Space Cowboy, where I’m talking about birds and bees and flowers and trees while I let the money people talk about money.Kiss my ass! That’s how you lose everything and you have no options. There is a mistake with people in my business where they think it’s going to keep coming in. Like all the rappers, who had the mansions and now they’re back at mom’s. I bought property. I own three houses. I want to have dough when I’m 55, so rock that.”

Luckily for Rollins, he was able to build his empire while still staying true to his art, and to himself.

Of that fine line, he says, “Ice-T taught me this years ago. You are a whore – you might as well learn how to be a pimp too and pimp yourself. The big mistake artists make is that they think people at the record company are their friends. If I drop below a certain percentage of sales, I don’t get past Reception. And so, I keep the integrity on, but I’m always looking to learn something and put some money in the bank because in my work, 100% of my income is approval based. When [the public stops saying], ‘Yay!’ I’m out of a job. Nobody but Ozzy and Sinatra and Mick Jagger get to go lifelong in this. Certainly not a mere mortal like myself.”

Mortal maybe; mere, never. His drive is always shifted into first, his pedal to the metal.

“I’ve always had that vigorous sink or swim thing,” he says. “And I have it now. I always feel like I’m the guy in the mailroom. I always feel like I’m the opening band that goes on at 7:30 that no one’s going to see. I’ve never thought anything else.”

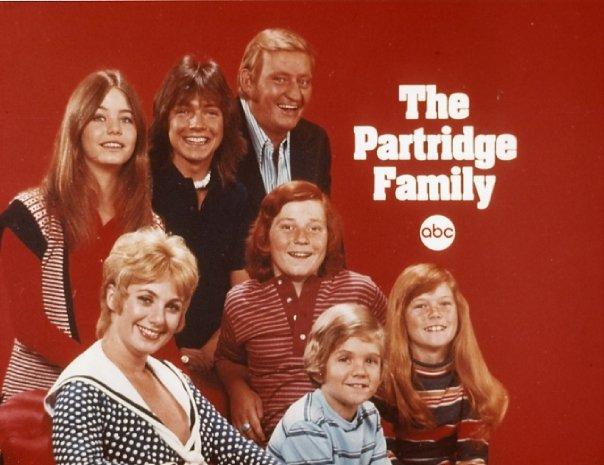

His early years with Black Flag mirrored this image of the muscular underdog, and also of the disciplined anarchist. This lifestyle, which seemed rambling but was actually very stratified and directed, stayed with him way past the expiration date. Of these hard-core pioneer years, he says, “We were a very ambitious band. We were doing seven shows a week, sometimes two sets a night. We were doing a record every seven or eight months, writing twenty songs at a time.”

Compared to this, his following project, the Rollins Band, was a picnic or no picnic, depending on whether you are Type A or Type B.

“With the Rollins Band, it was boot camp,” he says. “At band practice you turned the air conditioner off and closed the doors. Roasting hell. We practiced like Marines. The first show will be on point. We will fuck you up. No meandering. It was like, I’m on a mission. Here it is, motherfucker. It’s a lot of discipline. I’ve averaged 106 shows a year for 24 years.”

This is in addition to his quiet time, which is the closest Rollins will ever get to a Calgon bath. His writing, most of it all published and well-read by scores of fans who may have never even heard a word of his music, is another way to keep the demons to drop down and give him forty.

“I hate writing,” he says. “I just wish I could stop but I can’t. Writing is not a joy to me. The better you get at it, the harder it is, because it’s less time that you bullshit yourself. I’ve met a handful of writers and they’re pretty miserable people. Because they know that the beast is sitting in the room saying, ‘come on. You know you’ve been playing around with your friends long enough. Back to class.’”

And, of course, you don’t need to read Henry Rollins in order to read him. You can always find deep meaning in the tattoos, right on his person.

“I got started in ’81,” he says, “in those grimy places in Hollywood. Nowadays, you have to stand in line behind a model and a housewife, but not then. Society catches up with all of this. I wanted to be different. I wanted to customize the chassis. I used to think that by decorating the exterior you change the interior. I don’t get tattooed anymore, but I don’t regret anything that is on me. My first tattoo was a Black Flag logo on my left arm. Actually, that was the only one I ever really needed. You get one, and in your youthful bravado, you’re riding this rock thing until the wheels come off so you may as well get another tattoo.”

Adding to the list of surprises is Rollins’ musical tastes. It’s everything you would expect, and less. Picture the man, just him and his tattoos, sitting naked in a hotel room, on the phone with his credit card on his thigh, ordering the Time-Life collection of AM Gold from an infomercial. The story you’ve just read is true. Rollins can dig Van McCoy, Chicago, Kansas, Minnie Ripperton and “Rock The Boat” as much as the stuff you just know he likes and why bother asking.

He says, “As I get older, I find that the music I listened to on Casey Kasem on Sunday afternoons has a certain appeal now.”

You can add to this list everybody’s favorite guilty pleasure, William Shatner. Like Rollins, Shatner is both a show biz curio and an extremely gifted performer. The partnership seems as natural as it is unnatural. Co-piloting on the song “I Can’t Get Behind That” on Shatner’s latest album, Has Been, Rollins got to work with one of his idols, Adrian Belew from King Crimson. Belew, who lived down the street from the studio, was requested by Shatner in the middle of a recording session when he said, “Henry, we need a guitar.” This story, in itself, is not interesting, but the way Rollins does a Shatner impression is priceline – er, priceless. You simply had to be there.

Did Belew know who Rollins was? That’s a big 10-4. Could he rattle off even two of Rollins’ own songs? Most likely, negatory.

Of his degree of fame, which can range from feverish to frosty, depending on if you’ve reached the party to whom you are speaking, Rollins says, “I’m not a multi-platinum artist, so they’re not camping out on my lawn. I don’t need security to go to the grocery store. People recognize me all the time at the grocery store or at the hardware store. Do I get talked to a lot? Yes. Do I get recognized? Within one traffic light. The car next to me. Within a minute of walking to any hotel, airport, restaurant, store…within a minute. I see my name being lip-synched by someone pointing at me. It comes with. But do I have to run frompaparazzi? No. They want the young, handsome guy with the hot chick. Not the short graying man who walks alone. I’m so not interesting to these people. I can’t tell you how little they give a fuck, which is fine. It allows me to do what I need to do.”

And what he does, whatever and whenever, he usually does alone.

“The girls in my office say that I’m dysfunctional and I’m losing the plot,” he says. “[They say that], ‘you don’t know anyone. Your phone doesn’t ring.’ And they’re right. I go out on Friday and buy a whole weekend’s worth of food and I hope that the phone doesn’t ring. I do a whole weekend’s worth of reading and writing and thinking. The girls in the office say I don’t know how to relate, but I get the work done. I’ve always lived alone. I’m the loner type. It makes sense to me. I have no interest in being married. There used to be a lot of rumors about me being gay because there was not a chick on my arm, but I’m completely heterosexual. I’m just really discreet.”

That, and one large caveat: “No female would sign my pre-nup.”

The man walks alone, but he’s earned the path. He recalls something David Lee Roth had said, and he paraphrases, “you sometimes get shit from the guys at the watering hole who say, ‘it must be nice’ referring to your lifestyle. And [Roth] says, hey, we all started off as seniors in high school. You went for your dad’s bank job. I went for art. You took the easy road. I rolled the dice. Don’t be mad at me.”

However, just because he walks alone, doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a careful eye on you. Rollins is a regular Yankee Doodle Dandy, with the emphasis on the do or die. He says, “You gotta be a good American. You gotta help the old lady up the stairs. The cold guy gets a blanket. We all pitch in, whether you’re making $2.50 an hour or $2 million a year. I consider every American my countryman. Even if they’re in the Klan or not. They are my neighbor. I may not like them, but at the end of the day, I have their back. Bush, for instance: I’m not a fan. If he was hungry, could he have half my sandwich? Absolutely. I don’t like him, but I don’t want him to starve to death. I just want him to get a new job.”

Rollins sees his life as a series of new jobs, which keeps him from getting stale or soft. Of other performers who may not have his constitution, he states sadly, “[They] go out on the stage and you pour it out. And then they say goodnight and get so lonely afterwards. That’s why performers get into really bad self-abuse cycles. To come down from that performing thing, you either want company, or some kind of sedative…anything to get you down from it. Because it’s such an up. I can see the appeal of heroin. I can see the appeal of booze. Or people surrounding you and saying you’re great.”

Stating that he essentially lives his life like Indiana Jones, he says, “I just pick a country and I go. I’ve been all over Asia and Africa by myself. I just go. Yes, I’m very fortunate — but at least I’m not blowing it on dope.”

The workaholism that seeks to destroy him only serves to make him stronger, to the satisfaction of his millions of fans, now spanning generations. He says, “If there is work to be done, I’m doing it. You always learn something.”

This article originally ran in Popentertainment.com.